photo Simon Beckmann

“Joya: AiR is an arts residency for artists and writers. Joya: AiR describes itself as not only a unique, stimulating and contemplative environment for international artists and writers, but as a meeting point for divergent and creative thinking. The residency offers an ‘off-grid’ experience in the heart of the Parque Natural Sierra María-Los Vélez in the north of the Provincia de Almería, Andalucía.

My residency at Joya: AiR was generously supported by The Art for the Environment International Artist Residency Programme, an award to explore concerns that define the twenty-first century - biodiversity, environmental sustainability, social economy, human rights - and through their artistic practice, envision a world of tomorrow. I had proposed to make a new series of artworks sitting within the body of work called Future Geology. A self-initiated material futures project which I propose to conduct further research and material experimentation for during the focused period of the residency.

The gems on the image are a poetic translation of these topics (2014-15)

Future Geology

Future Geology focusses on the simulation of human effects on the earth’s crust. In the era of Anthropocene, human activities have a global impact on the Earth. The project addresses the effects of humankind depleting natural resources and polluting our soil. In reading rocks, we read the story of our restless planet. We come to understand its complex patterns of interaction and the nature of change over deep geological time.

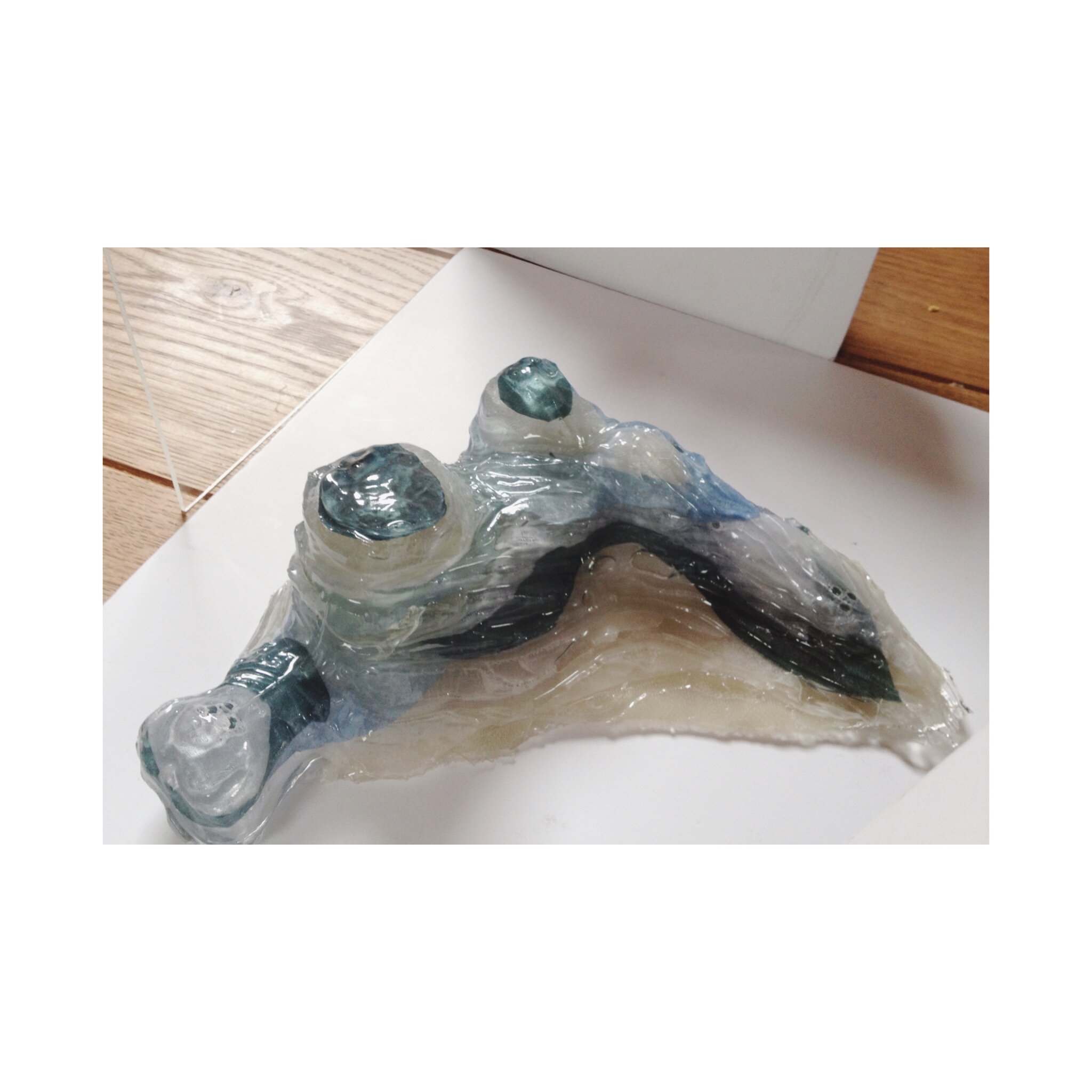

Therefore, I created ‘future stones’ over the past nine years; made of artificial materials such as metal, chemical resin, plastic, aluminium, concrete, textile, plaster, glass fiber and glass. In this project I am looking for new compositions that question how our soil can be used for aesthetic purposes, exploring the design opportunities presented by recycled materials. Over the last years I have been refining the sculptures and adding onto it. This artist in residency helps to crystallise my creative practice further and the image below shows one of the first sculptures of this ongoing project made in 2010.

First sculpture made of Future Geology (2010)

The JOYA: AiR experience

Grateful for the opportunity to travel to Joya: AiR I tried to approach the residency as a blank canvas in order to arrive with an open approach and allow myself to soak the environment up as much as possible. However, in preparation of the residency together with the research I conducted I did get an image on how Joya: AiR might be. A beautifully renovated artist in residency located in the “parque natural sierra de maria los velez” surrounded by an incredibly mountain landscape. On my arrival that was confirmed directly. At 8.30PM I got picked up at the bus stop Velez Rubio (the closest you can get with public transport). Simon friendly welcomed me and took me with his Land Rover over the rural country roads to the natural park. It is a 20 minute drive and that made that we approached the house steady but slowly while the sunset took place. A magical start of this amazing experience.

view from Joya: AiR

On arrival my expectations were more than true. The curators of Joya: AiR, Donna and Simon, greeted me with open arms and it was a warm (literally and figuratively) place to stay for two weeks. One of the most special experiences at Joya: AiR was the silence. Especially when being used to living in London, which is never silent or quiet, that was something that stood out from my very first day. It is an incredible valuable gift to experience silence, peace of mind and tranquility. The benefits of that has seeped through to my art. Granting yourself the headspace to sit and contemplate is priceless. I was distracted the very first days, because I am pretty addicted to being constantly productive. For me this felt very unusual and a bit uncomfortable to get used to as well. In English there isn’t a specific word for it, but in Dutch we call it “niksen”. These very first days of “doing nothing” gave me new insights and ideas and I started to love it. I would usually go on a morning walk before it got 36 degrees outside. I would walk through the valley, climb a mountain or sit under a tree to observe and generate ideas. After a couple of days I started making and realising ideas that weren’t part of the plan.

landscape around Joya: AiR

Apart from the contemplative aspect of the residency, the social contact and community aspect was an important part of the experience as well. We would present our work to each other, share perspectives on particular subject and generate ideas on how to make a living as an artist. During the day the artist would work individually and approximately every second evening one of the residents would present their work followed by a tasty dinner party where everyone would share thoughts and ideas. Sharing stories, experience and food was absolutely an added value and contributed to the many fruitful conversations I had.

supper time at Joya: AiR

sunset at Joya: AiR

Outcome

As a multi-disciplinary artist my work always involves creative research, narratives, installation art and material innovation. During residency I developed and discovered the potential of these Future Geology materials further. For this edition of Future Geology I focussed solely on plastic and created rock formations made from household waste or plastic found in nature. These artificial rocks I photographed in nature to start a dialogue with the viewer on when nature starts or ends. And when a landscape finishes or ends. The findings of the work I made in the first week were translated in the series of sculptures I created in the second week.

Photographs out of photographic serie made at JOYA, Future Geology (2019)

During the artistic research about plastics and landscapes I found out that the region Almería in Spain contains a plastic sea. This involves 30 miles of white plastic greenhouses. Once a year the plastic needs to be replaced and the plastic sheets are dumped on the land. This resulted in land covered with plastics which are meters high. Even though, I didn’t have the possibility to visit this region myself, it does resonate with my project and the research influenced the formation of the project Future Geology.

Plastic Sea from an aerial perspective, Almeria, Spain

In many aspects my time at Joya: AiR was valuable. Personally as well as professionally. Beauty, silence, environment and headspace was enriching and nourishing. Granting yourself the time to re-work and revise is priceless. The off-grid experience in rural Spain made me also critically look at my own living environment on an off-grid narrowboat in London and ultimately the amazing insights and conversations with the fellow residents is absolutely something to cherish.

Impact and future plans

At Joya: AiR I got the opportunity to expand and create a new body of work. Besides that it also gave me the unique opportunity to think about my future plans. What is next and which ambitions do I want to realise and prioritise. My time in rural Spain was an inspiring and great input to crystallise my future plans. As an environmentalist this influenced not only my perspective on my work, but also on my personal life. The residency is off-grid and carbon neutral. It was very interesting to hear the presentation by Simon about their story and in particular the water life cycle. It is a tricky thing especially in such a dry area. Also the electricity is generated in a sustainable way with photo voltaic and wind energy. That made it an inspirational source in itself as an artist working with the environment. On top of that, the experience also made me look at my own living environment. In London, off-grid and on a narrow boat. Totally self-sufficient as well but in a completely different manner. Some parts of this do overlap, but others differ. This made me look at my current living critically. Thoughts about how improvement could be made for me personally but also for the waters of the canal river trust. This might result in a future project. In the next 6-10 months I would love to find a suitable place in London to exhibit the collection of Future Geology artworks. Besides that I am looking into future opportunities on living on a narrow boat floating over the London canals. I do have the ambition to create, form and make my own boat from scratch and make it a platform for the future. Not only fuelling my own ambition, but also serving tourists, visitors and Londoners”.

Gwen van den Bout

Biography

Gwen is a London and Rotterdam based conceptual artist, graduate of a masters in Narrative Environments at Central Saint Martins, University of the Arts London. In her work she translates stories into interactive and sensorial spaces where the audience can explore her work intuitively and create their own meaning. Gwen makes art installations, curates exhibitions and creates sensorial brand experiences. Gwen previously studied at two universities in the Netherlands where she completed a BA at Breda University of Applied Science and a BA at Willem de Kooning Academy Rotterdam. She gained industry experience at several museums and cultural festivals, as well as with luxury retail companies, including working as a Visual Merchandiser for de Bijenkorf, the largest department store in the Netherlands. Gwen also won an open call from the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam to exhibit her contemporary installation artwork at the museum. Looking to the future, Gwen is focused on working in multi-disciplinary environments where she can communicate stories – ranging from exhibitions in museums, intuitive installations and outstanding window design. She is passionate about participative culture and bridging the gap between the commercial and cultural worlds.